Ishaan’s mother refused to come downstairs to our Christmas party, pouting in her room for the evening instead.

“She doesn’t feel like we’re welcoming her,” Ishaan hissed at me as our guests arrived.

Towards the end of the evening ten or so of us began playing that game where an apple is passed between everyone’s chins around the circle. Ishaan, my fiance, was seated next to a friend’s boyfriend, and when he realized he’d be neck and neck with him, he shot up and declared to the room, “I’m not GAY.”

His words screeched the party to a halt. Eyebrows raised into hairlines and chins receded into necks. Half the folks there were gay and/or bisexual, including me. I was living a straight lifestyle but I wasn’t closeted. Ishaan apologized to me in bed that night but our life together was unraveling and we both knew it.

I’d been sleeping with all kinds of people since I started sleeping with people at seventeen, but my long term relationships until Ishaan – and ending with him – were with men.

Our culture trains out of us the messier, harder to define betwixt spaces within, urging us to pick this or that, and chastising those of us who don’t, won’t, or can’t. And if your natural place of belonging is betwixt it might be possible to hide from yourself until it’s reflected at you histrionically, like my fiance’s declaration. The reason it took such drama to wake me up and claim myself is that I hadn’t noticed that I’d pitted my desire to be a mother against my queerness.

At 32, all my actions were bricks laid upon an undeviating path towards motherhood. My awareness and desire didn’t include being gay and bi and being a parent – not that I was exactly gay. Nor did it include single parenting like my mom had done. Depending on your generation, you might be thinking, of course you can be gay and bi and be a parent. And you’re right, that’s true now in many places. It was also true then but the price for that life had never been one I wanted to pay. Being a mother meant needing a husband to me at the time. Not that I was so into state-sanctioned marriage, it was the stability I was chasing. Same sex marriage was recognized federally in the U.S. June 26, 2015, almost four years after I left Ishaan. I hadn’t realized that my desperation for motherhood had been a turning away from queerness. Both hadn’t felt available.

It was easy for me to pass as the person my culture taught me to be until it wasn’t. I never believed in coming out – othering myself to my communities – or defending my right to exist. We exist because we are here existing, full stop. And I still believe this. It was an act of self love to refuse to come out, a bravey-cat move for young me coming of age in the late 90s and early aughts. The problem with choosing not to other myself was that in our current culture, it created invisibility, even to myself. My family was basically fine with whoever and whatever so I never had to stake claim the way people did sometimes, with the officiality and potential banishment.

After almost a year and a half together, Ishaan and I got engaged. He was a brilliant and hot software engineer from Delhi. Ten days later his mother arrived, also from Delhi, and Ishaan became unrecognizable to me. He went from sweet-natured and good-humored to angry and derisive. His mother, meanwhile, was in our kitchen, rearranging it to her liking, filling our cupboards with utensils and other items she’d brought from home.

I still have the necklace I got for Lasya as a welcome gift. During the six weeks I endured Ishaan’s about-face and Lasya’s hazing, the necklace walked through the fire of discernment with me. It turned out that it was for me all along, a symbol of my self love. And when Ishaan went through my jewelry box one day while I was at school, taking back the various bracelets and bright gold items his mom had given me upon her arrival, he didn’t touch that necklace.

I had done as Ishaan instructed, presenting the gift to his mom upon meeting her. At $235, it was the most expensive piece of jewelry I’d ever purchased. Handmade by a local artist, the center pendant, an elegant filigreed circle with a large open square in the middle, was 14 karat gold, and along the chain were understated semi-precious stones. As Lasya unwrapped my gift the corners of her mouth turned down and she grimaced as if what I’d given her was a gumball machine doodad. She slowly put it back in the box, wrapped it back up, and pushed it back across the table to me, refusing to accept it.

Ishaan had explained that I was to call her “mummy” out of respect. But her habit was to call me things like unintelligent and untalented and then walk away, refusing to respond when I told her adults didn’t call other adults these sorts of things. So I began calling her by her first name, Lasya, instead. There are many more sensational details from this time, and though titillating, they’re not what this story is about.

Lasya’s dislike of everything that I was, her insults, backhanded actions, expanded through reversal, my own capacity for self love.

I would become a mother but not like this.

Ishaan’s final words to me were, “Leave the keys under the mat after you’ve moved out.” The day after Christmas my family came over to help me pack and move.

When Ishaan tried to get back together with me that summer, after Lasya returned home, I said no thank you but we met up to talk.

“You’re dating a woman now, huh? I saw it on Facebook,” he asked, all hints of hostility gone from his tone.

“Yeah, I am. And I’m really happy.” I was dating a couple different people but he didn’t need those details.

He wasn’t open to being friends so we said goodbye.

“I hope you have a really good life, Ishaan,” I said. “I wish you all the best.”

I hugged him, smelling the scent of his skin for the last time.

I spent the next year underneath a lot of beautiful people. I began claiming my queerness and eating pussy in earnest. My gay uncles shuddered when they heard me use the term queer to describe myself as that word was still transitioning from slur to identity.

The night gay marriage passed in Washington State was December 3, 2012, almost a year after I left Ishaan. The streets of the Pike Pine corridor on Seattle’s Capitol Hill were in rapture. The city watched the election results from restaurant televisions and when the news broke the euphoria could not be contained within walls so the people hit the streets. We walked around googly-eyed and beaming at one another, our hearts aflutter in our rib cages. We could get married. We could get legally married. The ability to “get married” truly matters when your people have been kept from it and the protection and stability it provides; it was a different way to walk down the street. My gay uncles were the most stable relationship of my life but they were not protected legally as a couple. Instead they were “card-carrying homosexuals” as my uncle put it when he showed us the domestic partnership cards they kept in their wallets.

I’d never been in such a large crowd that was also so wildly peaceful. The love bubbled up, glistening. It gurgled over the edges even. We held and hugged each other, perfect strangers, now linked by the reflection and affirmation of our existence and right to be recognized and protected as couples by our culture. You could inhale the delight into your lungs and the night sky had become all sparkly, as if the stars themselves had descended from their cosmic lofts to celebrate with us just atop the buildings.

Forest Iverson

Seattle, WA

Read more articles by Forest

Orgasm for Survival

Orgasm. The brink. The edge. The what’s so of our world. Both the stir and cauldron of creation. The hallway of myth making. We use it to bring us to our knees and then to stand back up again. To process. To engender. To behold. To not only resist wrong...

Leading My First Bodysex Retreat

With the goal of warmth and groundedness I took my time setting up my living room over a couple days and it came together fabulously. There aren’t neighbors on any side of my house but I covered the windows with altar clothes I’d purchased at the main temple in...

Choosing to Align

Last summer I started using my masturbation practice to process some things only to remember a past me also did this, though not in front of a full length mirror with a pile of toys, oils, and lube next to me. It was in ancient times before the pandemic so I’d...

My Preferences

Choosing the Discernment of Verisimilitude Over Nescience By Way of Preferences They weren’t a bad lay, but we were quite mismatched in terms of a lasting relationship. We were fucking one night a month or so into discovering this about each other and then, rather...

Orgasms Aren’t One Way

Once safely out of the driveway, I unbuttoned my pants, grabbed the vibe from the passenger seat where I’d tossed it as I’d gotten into the car, and clicked it on. It felt good over my jeans. Driving masturbation is a delicate balance between your inner eyes settling...

Arousal Is Interesting

In 1992, just before the ninth grade I got braces. And headgear, which I was told to endure for 22 hours a day, but only wore at night because I just couldn’t wear the contraption to school. My orthodontist hung polaroids of his patients in their various stages of...

A List of Things That Have Been Inside of My Vagina

Q-tips - when I was in early elementary school, this was more exploration than turn on. Tampons - When organic tampons came on the market I only bought those. And once, I got some organic ones from Target and took them on a trip to a remote location in Arizona, far...

Pleasure is Radical

I’ve been struggling with the blog topic of pleasure because each time I start to write about the yumminess of it, what swings in bombastically and unannounced are the injustices and wrongs of our time, the many tasks I need to attend to, and all the things my monkey...

Anger and Our Wild Selves

“Betty used to say, ‘Women need to get in touch with their anger and they need to do it all the time,’” Carlin said as the group of us discussed this month’s blog topic over zoom. “Pleasure connects us to our anger,” said one writer. “I actually have a really hard...

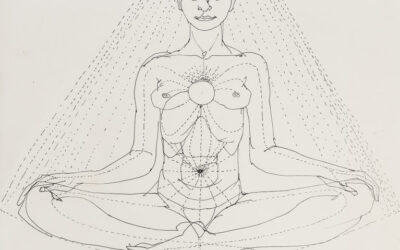

Menopause Resources Recommended by Forest

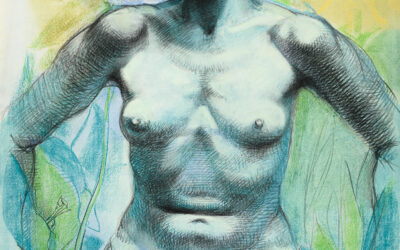

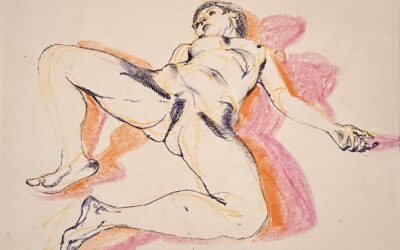

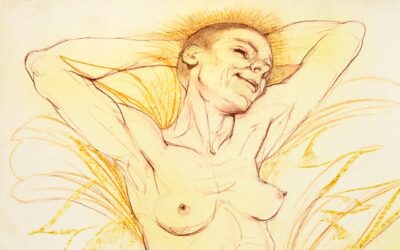

Art by Betty Dodson No one is paying me for this compilation. I’m just sharing my bumbling around and what’s worked. I hope you find it helpful. I also don’t necessarily agree with 100% of what each source preaches. Please also take what resonates and leave what...